DIGITAL PRINTS, UNWANTED STEPCHILD, OR HOW I

LEARNED TO LOVE THE NEW TECHNOLOGY

By Steven Dornbusch

Confession

I must confess, I have never touched an engraving plate, or pulled a screen print.

According to accepted definitions, I am not a printmaker at all. I do not use stones,

blocks, or plates, acids, washes, or inks. I do not get cut, or dirty, breath harmful

fumes, or need upper body strength. I work alone, with near complete control of my image

from start to finish.

Yet I make prints: Iris prints, laser prints, and ink-jet prints, limited edition prints on

fine archival papers. I have exhibited them, just as I have exhibited my sculptural work.

Whether my Prints are good, mediocre, or unacceptable, depends not only on aesthetic

judgment, but also on the operative definition of original fine art print.

From the Barricades to the Salon

From time to time, the upstarts shake up the academy. From my

side of the Atlantic, the R.E. after many of the names associated with

Printworks looks a bit stuffy - a Royalist holdover from previous times.

Actually the R.E. stands for Royal Engraver, a proud hundred-year old

moniker that memorializes a successful past struggle against critical

hostility.

Lounge crooners the world over sing Mack the Knife, obscuring The Three Penny

Opera’s avant-garde origins. The ghosts of Kurt Weil, Scott Joplin, and Duke

Ellington rub shoulders in the establishment. The output of the revolutionaries eventually

becomes the status quo.

A century ago, it would have seemed aesthetically laughable and

financially idiotic to collect a large commercial screen print by Henri

de Toulouse-Lautrec. Today it is more than a safe bet, like collecting

Impressionist art. All screen-printing was once excluded from the fine

art print family. Today, a lingering Inferiority Complex survives; many

still prefer the more ‘high falutin’ term ‘lithograph’

over ‘screen print.’

The Digital Printmaker

Artists

have been making digital prints for years now. I started experimenting

in 1984 with my 512K Mac and a black ink daisy wheel printer (Remember

those?). The tools were so primitive that I felt like I was making potato

prints with my ‘wrong hand.’

Artists

have been making digital prints for years now. I started experimenting

in 1984 with my 512K Mac and a black ink daisy wheel printer (Remember

those?). The tools were so primitive that I felt like I was making potato

prints with my ‘wrong hand.’

In the early 1990’s came the sophisticated painting/drawing programs along

with powerful computer processing chips and memory storage capabilities needed to run the

new applications. These programs are enough to make many an artist salivate.

The capabilities include a reputed 2.4 million colors, layering, multiple masking,

perfect registration, truer colors, unlimited collaging of images, resizing, expanded

tinting, and the ability to save earlier versions of a work. While some of these

capabilities mimic those in hands-on printing, others far surpass them. True, I have lost

work to glitches, suffered a frozen digitizing pen, been unhappy with output colors, and

frustrated by output size restrictions. But it is the advantages of digital over hands-on

printing that attracts me to the medium.

Why Make Digital Prints

What

artist has not been well along a significant road only to make the wrong

turn and ruin a work? How wonderful to return to the fork in the road,

where the errant turn was made, but this time choose the right path.

When I ruin an exciting ‘painting,’ I have the option of returning

to an earlier saved version, and starting back from there. In my Print

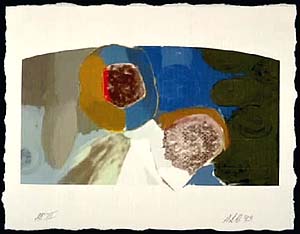

Triad, I tried more than twenty different ways to fill, overprint, and

blend a masked bubble-shaped area, until I got it right.

What

artist has not been well along a significant road only to make the wrong

turn and ruin a work? How wonderful to return to the fork in the road,

where the errant turn was made, but this time choose the right path.

When I ruin an exciting ‘painting,’ I have the option of returning

to an earlier saved version, and starting back from there. In my Print

Triad, I tried more than twenty different ways to fill, overprint, and

blend a masked bubble-shaped area, until I got it right.

Why not enjoy the freedom of unlimited color mixing without the mess, risk, cost,

and time consumption of multiple pass screen-printing? I doubt I can see 2.4 million

colors, but that is how many my Mac painting application allows me to create.

Why not save the color palette of every ‘painting’ made? Inks run out,

mixtures dry up, and recipes never seem to produce quite the same color twice. I can

preserve my palettes forever. By sampling any area in a ‘painting’ I can also

create a palette from scratch.

‘Theoretical colors’ have advantages over printer’s inks. Imagine

incredible possibilities for under painting, washes, and off-registration blending, and

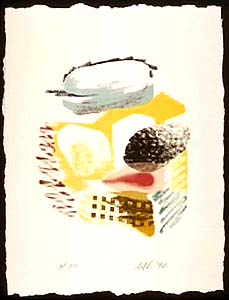

tinting. In my Print Recreation, I have a pink horizontal figure that overprints gray and

olive areas above, and below it. These perimeter areas are clearly tinted by the pink

figure. Yet they remain very visible, while the tint is still a rich saturated color

everywhere else. Printer’s inks preclude this. With the Mac, I mix a very deep color

(close to a black), and then tint at just seven to twelve percent. The best part is I can

even work backwards, starting with the final tint result I want.

Unlimited Collaging is possible without scissors and paste. Imagine if the

prolific American Artist Romare Bearden (1911-88) had lived another decade or two. He

could have scanned his many black and white original photos (or downloaded his own

original color or black and white digital photographs), color scraps from magazines,

pieces of cloth, or other media. He could have stored these images in vast libraries, used

them over and over, combined them in multiples, resized them, or tinted them.

Right now I am working on a series that alters and combines digital

photographs of the most commercial of squalor, Los Angeles’ Pico

Boulevard. I am collaging for aesthetic or formal effect, not social

commentary --fresh ways of seeing everyday visual phenomena. I like

to take my own images using my digital SLR. This allows me collage sources

outside the typical clipped (art directed) magazine spreads. Digital

collaging allows me greater originality.

Why Must Digital Technology be a Threat?

Digital

images can be stored, replicated, and communicated indefinitely. Unlimited

editions and no stone to deface or plate to destroy, offer a democratic

anti-commercial alternative to traditional fine art printing. They also

undermine the artist’s control over printing, papers, ownership,

payment, and piracy. For these reasons, digital printmakers share, no

less than the traditional print community, a pressing need to establish

standards of definition, originality, technical quality, and the like.

Digital

images can be stored, replicated, and communicated indefinitely. Unlimited

editions and no stone to deface or plate to destroy, offer a democratic

anti-commercial alternative to traditional fine art printing. They also

undermine the artist’s control over printing, papers, ownership,

payment, and piracy. For these reasons, digital printmakers share, no

less than the traditional print community, a pressing need to establish

standards of definition, originality, technical quality, and the like.

We computer artists must not wait for traditional printmakers

to come to us to establish new standards of fine art printmaking that

include us. We must propose tests for inclusion and exclusion. It is

not enough to require limited editions; is a scanned watercolor painting

printed on an Iris printer original? What kind of art is a collage of

painted pieces of photocopy? How about David Hockney’s Faxed prints?

Digital print standards must answer these kinds of questions. Neither

technology nor aesthetics stand still.

It is a cliché that the world turns faster and faster; fortunately or

unfortunately, it is true. Maybe artists are not getting better or smarter, but art

technology is. Printmakers, and indeed all creative people, need to keep up with changes

in the world. Authentic artists will always get the most from any tool or media. Digital

printmaking has much to offer these explorers. The wrinkles can be ironed out along the

way.

All Prints were drawn on a Wacom computer drawing tablet using Pixelpaint

software on a Mac cpu. They were printed on Frankfurt hand made

paper using a Epson printer. Printed in tabloid size, they were

hand torn down to

10" x 13" to define the edges of each Print. There was no use of a

scanner,

and no introduction of photography in these works. This series was entirely

computer composed and produced.

Photos, ©1998, William Nettles, Los Angeles

All art work and text © 1998 Steven Dornbusch

Some Other Printworks articles concerning Digital Art

Photoshopping for Photoetching

From Paint to Pixels

Conservation Standard Digital Printmaking

The information resource for printmakers

The information resource for printmakers  The information resource for printmakers

The information resource for printmakers